The recent and rapid rise of artificial intelligence(AI) has presented everyone with the pivotal question of how to adapt to the technology. The gravity of this question is especially evident in education, where teachers’ decisions on if and how to use AI in their classrooms directly affects how the next generation of students will learn.

To help staff at Terra Linda High School grapple with this adjustment to education, teacher librarian Kendra Rose and Visual & Performing Arts department chair Lisa Cummings have been leading professional development (PD) regarding digital literacy and AI. According to Rose, the school began to emphasize professional development focusing on AI during the 2024–2025 school year. “Students were definitely already using AI, talking about AI,” Rose said.

The TL staff had a PD day before the start of the current school year, which aimed to help teachers understand education in the age of artificial intelligence. “There’s two pieces,” Rose said, “How our students are using AI… and then there’s also how can teachers use it.”

A challenge for most teachers is the balance between preparing students for a world dominated by artificial intelligence while also ensuring that they develop necessary life skills. “It’s a very confusing time for teachers because we’re trying to do two things that contradict each other,” Rose said.

This difficult balance has put pressure on many teachers to adapt their curricula and teaching styles to best represent an increasingly AI-focused world. Although each teacher can decide how to adapt to artificial intelligence in the classroom, the subject that they teach plays a large role in this decision. In terms of how AI has affected the way they are taught, TL’s core subjects seem to be split into two categories — humanities and STEM.

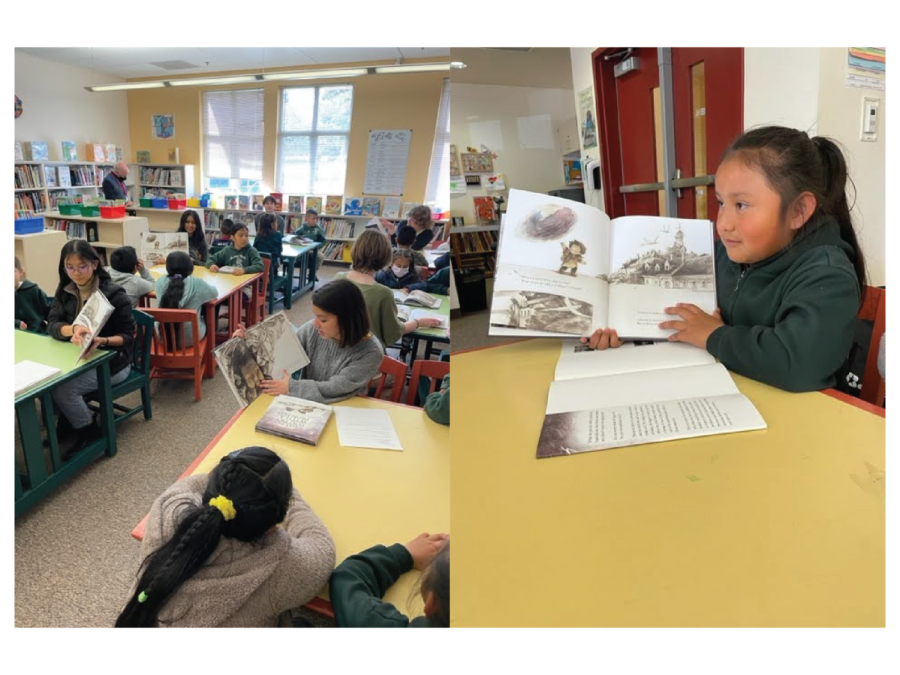

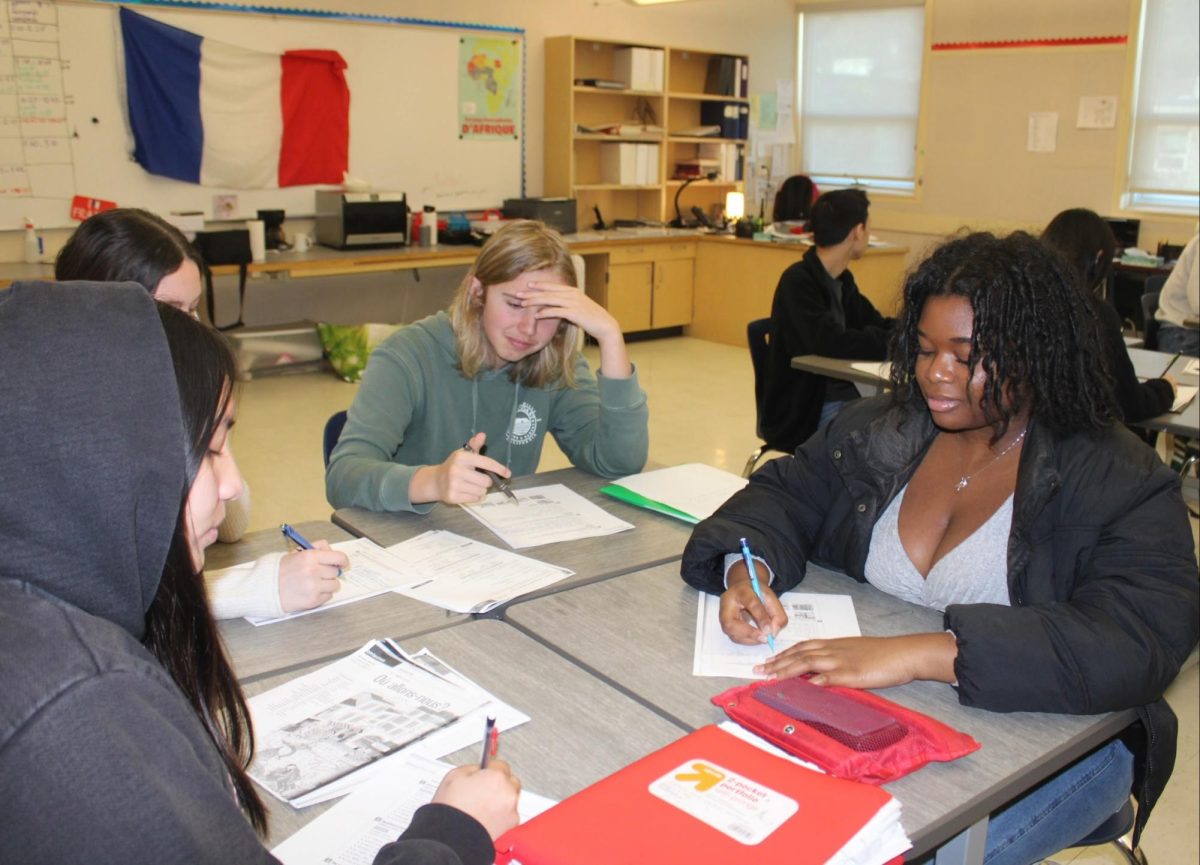

A common theme among the humanities subjects — English, Social Science, and Modern Language — has been a shift back to handwritten, in-class assignments. This is to ensure that students are learning and producing original work, as writing, a focal point of these classes, is one of the easiest things for AI to replicate.

With this greater emphasis on in-class work, teachers must be more attentive and adaptive during lesson time, according to English teacher and department head Dave Tow. “A lot more of what I do is responsive to what is happening in the room,” Tow said. “I think it’s made my job far more organic.”

Many teachers have been encouraging students to use AI on their own time, especially with the increased emphasis on more offline activities during class time. “Although [AI] could be a great study tool outside of the classroom, we will continue to encourage students to read and write and use pen to paper [in class],” said Erin Baskin, head of the Modern Language department.

Over the past several years humanities classes have been shifting away from substantial homework assignments, but Social Studies classes are an outlier in this trend. Many Social Studies teachers have continued to assign extensive homework, often in the form of readings and handwritten notes, because especially for AP classes, homework readings are where a large amount of learning is done.

Beyond teaching and assignment styles, the focus of many humanities classes has changed as well. According to Social Studies department chair Alex Robins, history classes now place far less weight on strict memorization. In the age of AI, the development of critical thinking skills is more important. “It’s about synthesizing information,” Robins said. “Not to gather information, but to use it.”

Alternatively, the core STEM subjects — the Math and Science departments — are adapting differently to artificial intelligence. Unlike the humanities classes, assignments in math and science tend not to be focused on reading or writing, so AI does not pose as much of an immediate threat to the development of skills and absorption of information.

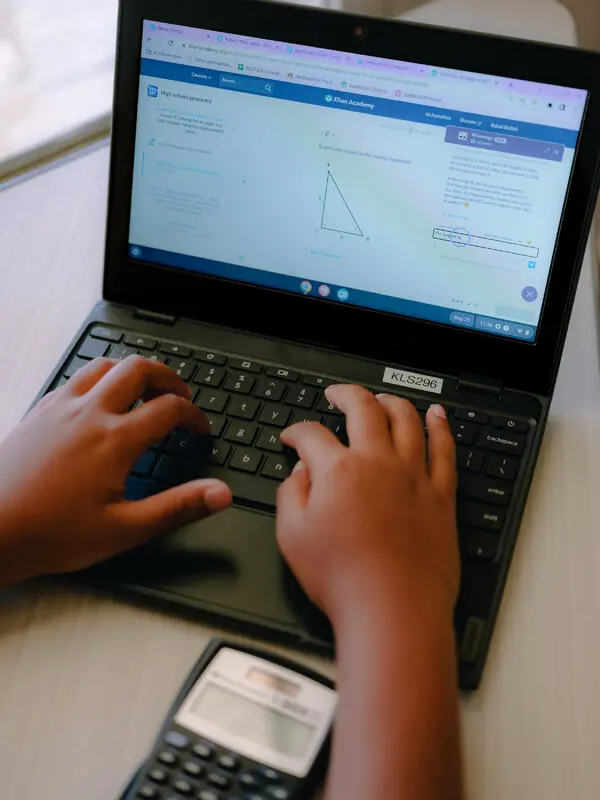

Of course, AI can still be a helpful tool in these subjects. Photomath — an AI software that allows students to take a photo of a math problem and receive step-by-step instructions on how to solve it — is frequently used by students for help in understanding and solving problems. But according to Melissa Millerick, head of the TL Math department, while tools like Photomath can be helpful, they often present students with more complex math than what they are currently learning. “It will answer a Calculus question for an Algebra 1 student,” Millerick said.

Generally, TL teachers have been encouraging students to experiment with AI for help outside of the classroom, but there have been several instances of effective student and teacher AI usage at school as well. Last year, English teacher Mackenzie Bedford had some of her classes utilize Khan Academy’s AI software, Khanmigo, to help students revise their essays.

Dr. Halcyon Foster, TL math teacher, previously used AI to test her math department’s ‘Problem of the Month’. “It would never answer [the problems] correctly,” Millerick said. “That was how [Foster] knew she had a good problem.” Foster no longer tests her monthly challenge problems this way due to moral objections against AI.

Artificial intelligence is still a relatively new technology, but it is developing rapidly. And while teachers across subjects have become more open about encouraging their students to use the technology for help, few have begun to formally incorporate it into their curricula.

But teachers themselves are still adjusting to the sudden rise of this technology, and according to Baskin, “As [teachers] become more comfortable using AI, it will be easier for them to direct students on how to use it themselves.”